Lessons Learned: Infrastructure Wins & Regrets at a Startup on Azure

- Introduction

- Databases

- Azure B2C

- Azure Functions

- Microservices

- Azure SignalR

- Managed identities

- App configuration

- Key vault

- Azure storage

- Application Insights + Log Analytics

- Monorepo

- Infrastructure as a code

- CI/CD

- .NET

- Playwright

- Cloudflare Stream

- Azure

- Conclusion

Introduction

Every startup wrestles with infrastructure decisions. Inspired by a post on building infrastructure at another startup, I’m sharing our own journey on Azure, sharing the lessons we learned and the specific Azure services we chose for our multi-tenant web application.

Building the perfect system architecture is an ongoing quest. Initial decisions, based on best guesses, can evolve as we learn how the system behaves in the real world. This iterative process is the art of trade-offs.

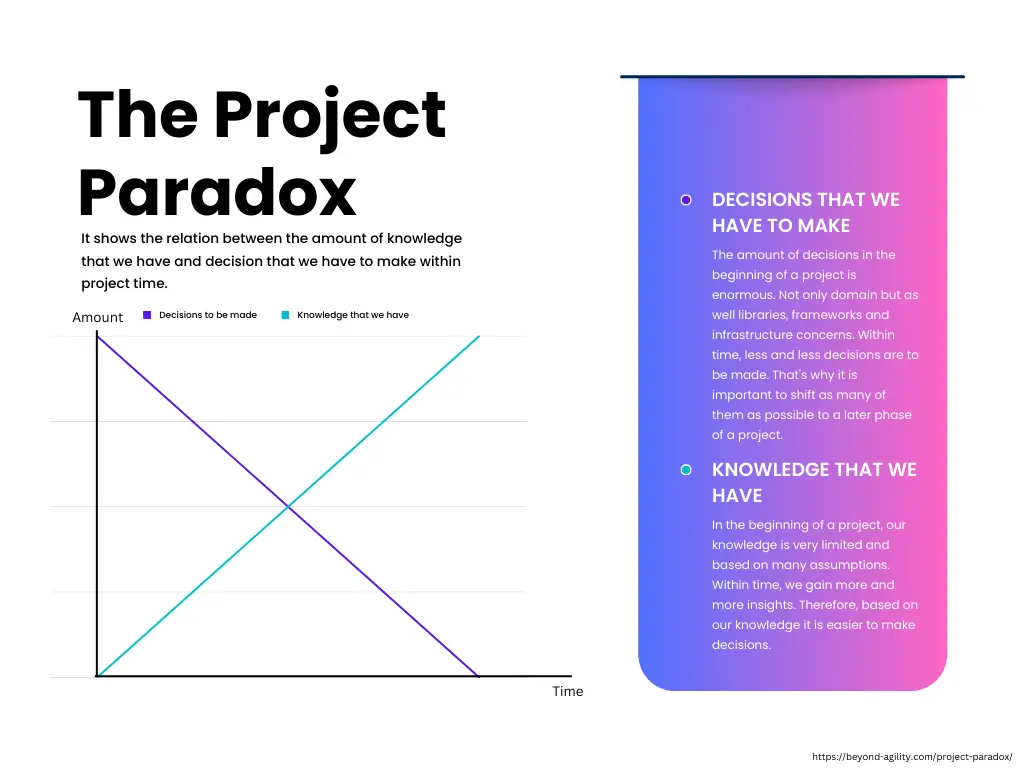

All startups and greenfield projects have in common the fact that at the beginning we know nothing, and we have a huge amount of decisions to make. This is called the “Project Paradox” - the concept I found on a cool GitHub repository - Evolutionary Architecture.

We always want to get it right from the start, but without real-world data, our initial solution might be overly complex or simply not the best fit.

Databases

There are significant advantages to using managed databases. They allow your team to concentrate on core functionalities and eliminate the burden of managing and maintaining self-hosted databases. We were thrilled to go this route, but our decisions regarding data persistence could have been better.

CosmosDB Gremlin

Initially, we chose Cosmos DB with the Gremlin API as our system’s main database due to our application’s social networking aspect and our “startup mentality”. We believed that a graph database would be the perfect solution for managing social network features like recommendations, likes, and connections, similar to platforms like Facebook and Instagram.

However, those decisions came with challenges:

- Our team lacked prior experience working with graph databases, especially Gremlin.

- We underestimated the potential for slowdowns and increased costs as data volume grew within the graph database.

- We used Exram.Gremlinq library, and while Gremlinq helped with code structure and readability, it has a limited community and documentation so required reliance on the author’s support (paid or free). Additionally, its syntax differed from core Gremlin. Translating working Gremlin queries to Gremlinq often proved time-consuming, and sometimes, achieving exact query wasn’t even possible.

- A significant portion of our data and relationships could have been effectively modeled using a relational database. The graph database added unnecessary overhead, leading to complex queries for simple tasks like retrieving data by ID.

public async Task<WorkshopDbQueryResponse?> GetWorkshopByIdAsync(string id)

{

return await _g.V<Workshop>().Where(g => g.Id == id)

.Project(p => p.ToDynamic()

.By(nameof(Vertex.Id), i => i.Id)

.By(nameof(Vertex.Label), i => i.Label!)

.By(nameof(WorkshopDbQueryResponse.Name), i => i.Name)

.By(nameof(WorkshopDbQueryResponse.Status), i => i.Status)

.By(nameof(WorkshopDbQueryResponse.Description), i => i.Description)

.By(nameof(WorkshopDbQueryResponse.SessionsInTotal), i => i.SessionsInTotal)

.By(nameof(WorkshopDbQueryResponse.SessionsPerMonth), i => i.SessionsPerMonth)

.By(nameof(WorkshopDbQueryResponse.SelectedCompany), i => i.Coalesce(_ => _.OutE<RegisteredWith>().InV<Company>().Fold(),

_ => _.Constant(string.Empty)))

.By(nameof(WorkshopDbQueryResponse.CompanyContact), i => i.Coalesce(_ => _.OutE<ManagedBy>().InV<ConsumerProfile>().Fold(),

_ => _.Constant(string.Empty)))

.By(nameof(WorkshopDbQueryResponse.Consultant), i => i.Coalesce(_ => _.OutE<ConsultedBy>().InV<BackOfficeProfile>().Fold(),

_ => _.Constant(string.Empty)))

.By(nameof(WorkshopDbQueryResponse.StartDate),

i => i.Coalesce(_ => i.OutE<IsParticipant>().InV<Session>().Order(x => x.By(y => y.PlannedStartDateTime)).Values(x => x.PlannedStartDateTime),

_ => _.Constant(DateTime.MinValue)))

.By(nameof(WorkshopDbQueryResponse.EndDate),

i => i.Coalesce(_ => i.OutE<IsParticipant>().InV<Session>().Order(x => x.ByDescending(y => y.PlannedStartDateTime)).Values(x => x.PlannedStartDateTime),

_ => _.Constant(DateTime.MinValue)))

.By(nameof(WorkshopDbQueryResponse.Provider), i => i.Coalesce(_ => _.OutE<ProvidedBy>().InV<ProviderProfile>(),

_ => _.Constant(string.Empty)))

.By(nameof(WorkshopDbQueryResponse.MembersCount), i => i.Coalesce(_ => _.OutE<HasMember>().Count().Fold(),

_ => _.Constant(0)))

.By(nameof(WorkshopDbQueryResponse.ScheduledSessionsCount), i => i.Coalesce(_ => _.OutE<IsParticipant>().Count().Fold(),

_ => _.Constant(0)))

)

.Cast<WorkshopDbQueryResponse>()

.FirstOrDefaultAsync();

}

Certainly, there may be simpler ways to retrieve this data, but it takes time to master all the nuances of Gremlin. As a result, your initial queries may look like the one provided above.

Don’t rush into using a graph database solution. First, gather data usage patterns. Identify specific functionalities requiring recommendations or complex relationship management, and then design a solution optimized for your use case. Storing “just-in-case” data in a graph database is inefficient. We found out that Facebook primarily relies on relational databases and creates graphs from them 1. Many social network services started with relational databases only and were able to scale to millions of users. 2

CosmosDB NoSQL

In my opinion, CosmosDB NoSQL is excellent, especially with microservices where it’s not that hard to model data in NoSQL as in a large monolith sharing tables. With the serverless option, you can build a scalable solution that costs you nothing when idle.

However, it is not a silver-bullet solution. Working with NoSQL can be counter-intuitive for people with a SQL background, and it’s likely that they will try to use the same approach for NoSQL as for SQL, leading to poor performance and high query costs. On a small scale, there’s no performance benefit of using NoSQL, so it’s best to stick to the technology your team is experienced with.

If you have SQL experts, start with a relational database that’s structured in a way that allows future splitting into smaller databases or migration (full or partial) to NoSQL. It is worth to mention that in NoSQL you would need to perform data migration from time to time, and it is way more complex task than in relational database.

It’s much easier to start with a relational database and move to NoSQL or graph later, rather than the other way around.

Azure B2C

We invested significant time in Azure AD B2C – three months just for the initial setup! It’s reliable, solid and cost-effective for low usage (free up to 50k monthly active users), but…

Everything relies on XML configuration. Even simple thing like POST request to your API after user registration require many lines of XML code, and there is no tooling available. We had to create custom scripts for managing environments, write custom policies in XML, and implement functionalities in our application code that B2C simply couldn’t handle.

Changes can take anywhere from 5 minutes to a whole day (usually 10-15 minutes) to propagate. Debugging becomes a frustrating exercise – massive JSON logs for error codes, with limited visibility through Application Insights.

There are definitely use cases for B2C, but for new projects, I wouldn’t recommend it as the starting point. Here are the options:

- Use an alternative service.

- Use an alternative service while planning your migration to B2C.

- Use B2C, but seek help from experienced professionals that will boost your deployment.

- If you’re not pressed for time, keep an eye on Entra External ID, the successor to B2C. It promises to address these pain points, but currently has limited functionality.

Azure Functions

Azure Functions played a role in our architecture, handling some recurring cron jobs that trigger webhooks and service bus events consumed by other services. While our functions are written in .NET8 and deployed in containers on an AKS cluster, there are key differences between .NET web apps and Functions in terms of configuration and code.

In our specific scenario, a small .NET service might have been a better fit. Here’s why:

- It offers a smoother experience for testing and debugging during deployments with same process across all services

- Since we’re already on AKS, we can leverage its built-in scaling capabilities based on factors like HTTP calls, service bus queues, etc. - functionalities that Functions handle natively.

Microservices

Microservices helped our development process. We could easily push code changes frequently (trunk-based development with continuous deployment) and test them automatically. But this modular approach also works with a well-designed monolith.

The big downside of microservices for us was managing them. As our business needs changed, we kept adding new code, breaking the boundaries, which created a big mess. It took a lot of effort to clean up and maintain all these separate pieces. In hindsight, starting with a well-structured monolith to get the core functionality before splitting it up might have been better. Luckily, Azure tools were really helpful during this whole process.

Whether you’re using microservices or not, AKS or App Services, it’s always best to start with your application in a Docker container. If you decide to migrate your app later, your CI process would remain unchanged.

AKS

At first, Azure App Services seemed perfect for our needs. They were easy to scale up or down, reliable and straightforward. But with our frequent deployments and custom scripts for swapping app service slots to achieve zero-downtime, things got overloaded. It turned out the App Service Plans we were using didn’t have enough resources to handle deployment storms with staging slots and swaps. It was often hanging on slot swap, blocking new deployments for an hour! Adding more App Service Plans would have cost us same amount as Azure Kubernetes Service (AKS) so we decided to try it.

AKS wasn’t strictly necessary from a technical standpoint. We were able to achieve things like handling traffic, staying reliable on App Services, but we didn’t want to adjust our development flow to technology limitations. AKS besides handling deployment storms, allowed us to implement some nice features easier like:

- Setting up temporary environments to test code changes (pull requests) by creating website with PR number prefix

- Automated managing our DNS records based on nginx ingress rules.

- Spot instances on AKS nodes to save money on infrastructure.

The catch? It took almost a year to get AKS set up to the point where we were fully happy with it. Of course, it was up-and-running in a few days, but fine-tuning the cluster and whole process was really time-consuming.

AKS vs. Running Kubernetes Ourselves

Managed Kubernetes services like AKS take a lot of work off your plate. If you don’t have a huge team or hundreds of servers to manage, a managed solution is the way to go. There might be some vendor lock-in, but the benefits of less work and easier management outweigh that.

Service Bus

After adding additional services, we found a need for these services to communicate with each other. Initially, we used HTTP calls, but this proved to be less than optimal. So, we decided to implement a service bus for asynchronous communication. Despite a learning curve, this turned out to be a significant benefit.

The service is affordable, reliable, and managed by Azure. It also provides a ready-to-use SDK and many useful features such as deferring messages, dead-letter queues, topic filters, passwordless authentication support, and much more. In my opinion, this is the best option for many projects that require asynchronous communication, without the need for Kafka’s features and complexity.

Azure SignalR

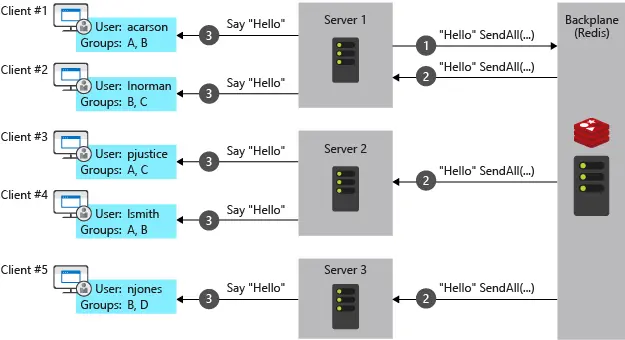

There is a subtle difference between Azure SignalR and the self-hosted version. With the self-hosted version, scaling your solution can be problematic, as multiple instances are not aware of each other. In such a scenario, you would need to add a Redis backplane, which increases the complexity of the infrastructure.

ASP.NET SignalR with Redis backplane

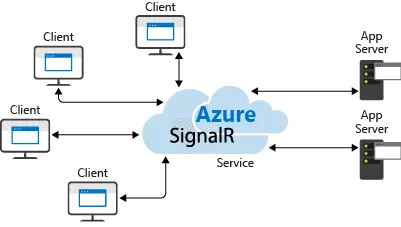

Azure SignalR operates differently as the service acts as a proxy, hiding all the complexity behind the managed service from an infrastructure perspective.

Azure SignalR

However, due to this difference, some features and configurations vary. So, when reading a guide, make sure to check if it’s for Azure SignalR or ASP.NET.

Managed identities

I find it hard to imagine managing an infrastructure without the help of managed identities. They greatly simplify the process of maintaining security! We use managed identities wherever possible to minimize the need for secret rotation, simplifies permission management, and enhance the developer experience by eliminating the need to store development environment secrets locally - everything is retrieved based on their Entra ID identity, so new developer can setup local environment on the first day of work! While this does create a slight vendor lock-in within the application code, the trade-off is definitely worth it.

App configuration

When we shifted from App Services to AKS, managing configurations became a challenge. Some parts of the configuration were stored in appsettings.json, some in terraform, and some in helmfile yaml files. However, once we moved to app configuration, our difficulties were resolved. Now, everything is centralized in one place, and we can easily retrieve all the configurations from the service. You can read more about app configuration in my recent blog post - Centralized Configuration with Azure App Configuration

builder.Configuration.AddAzureAppConfiguration(options =>

{

options.Connect(new Uri(builder.Configuration["AppConfiguration:Endpoint"]!), new DefaultAzureCredential())

.ConfigureKeyVault(keyVault =>

{

keyVault.SetCredential(new DefaultAzureCredential());

})

.Select("shared:*")

.Select($"{builder.Configuration["ServiceName"]!}:*")

.TrimKeyPrefix("shared:")

.TrimKeyPrefix($"{builder.Configuration["ServiceName"]!}:");

});

The code snippet above shows how we retrieve all configuration for the service during its startup in program.cs. By using DefaultAzureCredential(), it works both with the local developer identity and workload identity when running on the cluster.

Key vault

Simply put, you should use it.

Azure storage

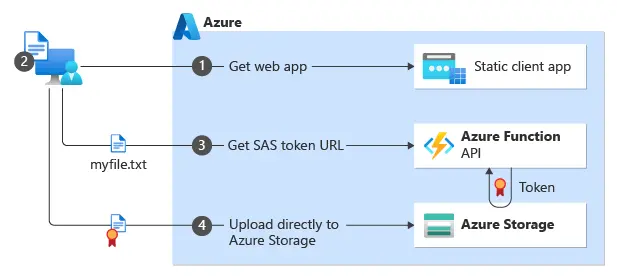

We use Azure Storage for a variety of purposes, including video streaming, image hosting, log storage, static front-end for Azure B2C, terraform state, and distributed logs. You can essentially build an entire product on Azure storage and Azure function, which will generate SAS tokens for storage operations.

However, be cautious with SAS tokens. It’s difficult to control how many are active, who owns them, and their scope. They are easy to misconfigure, potentially allowing access to other users’ data or permitting usage for longer than necessary. If there’s another option, avoid using SAS tokens. If you must use them, pay close attention to scope and lifetime settings. For example, for direct image upload, you can limit permissions to an exact path like /images/profile-name/image-name.jpg with a 5-minute lifetime. This way, even if someone tries to misuse or steal the SAS token, they can only access or alter a single image for 5 minutes, instead of all the images in case SAS token would be generated for /images/profile-name/ or /images/ path.

Application Insights + Log Analytics

We’ve established Grafana + Loki for some dashboards and stout/sterr logs display. However, the backbone of our monitoring and observability lies in App Insights. It’s a robust service that is incredibly easy to set up and use. Initially, it might be overwhelming because setting it up with default settings can result in gigabytes of logs, which count towards your bill. We’ve optimized costs thanks to Thomas Stringer article - Azure Monitor Log Analytics too Expensive? But, once you filter out unnecessary data, it becomes an affordable and powerful tool that gives you an end-to-end view of your application. All you need to do is add an SDK and provide a connection string in your app.

Monorepo

I prefer working with monorepos. This doesn’t necessarily mean having one repo for everything, it could be a backend monorepo, frontend, or all-in-one. I find this setup appealing, but if you’re comfortable with a different setup, don’t let anyone convince you that you must switch because it’s “better”. Both setups have their pros and cons.

Infrastructure as a code

From day one, we chose to manage our infrastructure as code using Terraform. This was a significant overhead, especially during the stage where we were continuously redesigning things. However, it was worth it. We didn’t encounter a single issue related to configuration drift between environments. Plus, when we hired a new DevOps, he was able to confidently create infra PRs within his first week.

We also implemented a subscription per environment and divided our code into layers based on the lifecycle and frequency of changes. For example, shared clusters and service buses were managed in layers that were rarely changed, while most changes were introduced in each service template. Additionally, we implemented a naming convention which simplified infrastructure management. When we received a request to create an exact copy of our infrastructure in another tenant, it was just a matter of changing the project name, which was the resource prefix. You can read more about this in my recent blog post - Getting Cloud Infrastructure the DevOps Way

CI/CD

From day one, we utilized CI/CD (GitHub Actions). Similar to Terraform, it posed an overhead but quickly proved its worth. It equipped our developers with confidence, knowing that if bad code was pushed, it would fail during the CI or CD phase. This also gave us visibility and the ability to connect application bugs to specific changes in the codebase. Every minute spent on CI/CD was worth it.

GitHub Actions

When I started using it more than two years ago I was very dissatisfied (lots of outages, issues, and missing features). Currently, I wouldn’t switch to anything else, and I recommend it to everyone who is considering migration from legacy CI/CD system or starting a new project

.NET

We have no complaints about choosing .NET. It’s fast, offers many mature, ready-to-use packages, and debugging is quite straightforward. It doesn’t consume many resources on the cluster and integrates seamlessly with Azure tools. It has a large community backing it, so it’s unlikely you’ll run into a problem without finding a relevant issue on GitHub or Stack Overflow. It’s also easy to find experienced developers in .NET stack.

Playwright

Due to our development flow, we heavily rely on automated tests. Playwright performs its job perfectly, finding issues that other types of tests may miss. It has a large community and is simply better than Selenium. I highly recommend using it.

Cloudflare Stream

We initially hosted videos directly from Azure Blob which was really smart decision because of very short implementation time, but encountered issues with some video formats played directly from the storage. This necessitated adding another service like Azure Media Service or moving videos to a third-party service. Based on the information on Cloudflare’s website, we decided to use their Stream service, but it proved to be a headache.

- The documentation wasn’t up-to-date and lacked crucial information, which we could only discover by experimenting with the API, which didn’t provide much clarity when errors occurred.

- There’s no .NET SDK.

- It lacks some core functionalities, such as the ability to set up separate accounts for development and production under a root account - this is only possible if you have a signed agreement with Cloudflare.

- There’s no customer support unless you’re an enterprise customer, even for paid customers - you can only create a topic on the community forum.

We thought that integrating Cloudflare Stream would take a week, but it ended up taking us about a month. Besides that it has very fair pricing model where you are paying for storage in minutes stored (not gigabytes), and for minutes displayed (not data transfer) which makes this service very affordable and easy to predict the costs with increasing scale.

Azure

It’s stable and meets our needs. While I believe we could achieve the same results with another cloud provider, we greatly benefit from using the Microsoft stack - Azure, .NET, GitHub Actions, VS, etc. We wouldn’t replace it with any other cloud.

Founders Hub

It’s no secret that we applied to the Microsoft Founders Hub program and received substantial help from Microsoft. In addition to Azure credits (ranging from 1000 USD to 150000 USD), you will receive GitHub Enterprise seats, Visual Studio Enterprise licenses, OpenAI credits, Microsoft consultations, and much more 3, all without any commitments. This is great for any startup.

Conclusion

Dream big, but start small. Don’t try to solve problems that you aren’t facing yet - align with current needs and challenges.